The decision of the European Central Bank to keep interest rates during 2017 in Eurozone under their historical minimum, with the key reference rate at zero, as well as to leave their substantial public and private debts accumulated since 2015 operational was followed by this institution’s decision to leave the marginal lending rate at 0.25 percent, allowing banks to borrow for 24 hours.

The assertion has been made that, with prevailing zero interest rates, banks gain the capability to self-fund at no cost from the European Central Bank (ECB). Consequently, banks are expected to reduce the rates they impose on customers who are indebted to them. The ECB’s historically low rates exert an automatic impact on short-term savings. As banks cannot afford to disburse substantial amounts in cash, they are constrained in lending at favorable rates without compromising their profit margins.

The ECB recently unveiled a series of monetary policy measures, including a reduction in its central rate to zero for the first time in its history and the introduction of an extended long-term loan facility for banks. The initial phase of this plan has unfolded mostly as intended. However, since the implementation of the ECB’s financial strategy, citizens across the Eurozone have observed a decline in average salaries.

In essence, when the ECB lowers its interest rate, it aims to stimulate credit activities and consequently boost investment. Conversely, an increase in the interest rate signifies a tangible risk of inflation, where an excess of cash circulates while prices surge rapidly, necessitating proactive management of the situation. In the current scenario, a political risk emerges as a primary challenge for the year. The ECB authorities are acutely aware of this and are prepared to take necessary measures to prevent market upheaval, even if their actions may exacerbate the situation.

While there are no imminent announcements of new decisions regarding interest rates, the initiation of monetary contraction seems untimely, especially considering upcoming key elections in various countries and a backdrop of escalating populist movements. The ECB is understandably reluctant to face additional uncertainties.

Given the ECB’s investment in short-term products, it is the capital that is predominantly affected by the zero rates, particularly commercial paper issued by corporations. Prolonged stagnation refers to a situation of feeble growth characterized by persistently low, or even zero, interest rates. Currently, there is a recovery of growth and inflation in progress. The demand deficit is not insurmountable, and as additional savings are anticipated to be reinvested, efficiency is expected to rise.

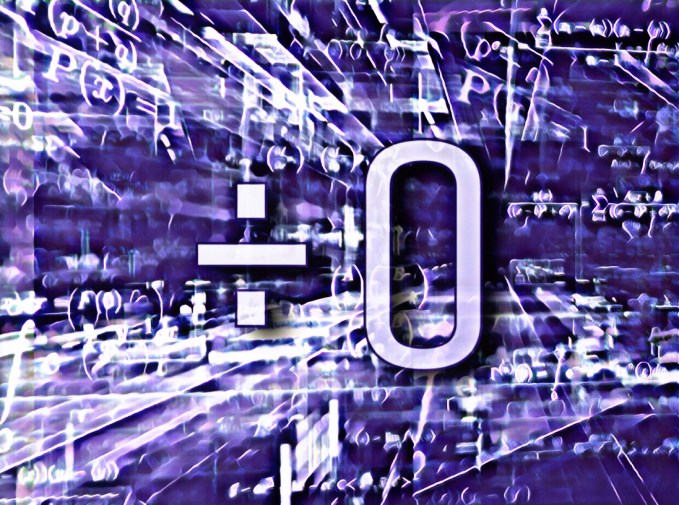

To address these economic dynamics, the ECB has opted to initiate an extensive asset purchase program, surpassing previous initiatives. The Quantitative Easing program, initiated in March 2015, involved monthly purchases of private and public bond securities on the secondary market totaling 60 billion euros. This decision was prompted by the collapse of inflation and the looming risks of deflation in the Eurozone. Furthermore, zero and especially negative interest rates are symbolic of absurdity, as zero in a range of values conveys the message that no other points exist.

Overnight deposit rates, which entered negative territory for the first time in June 2014, were maintained at -0.4% and strengthened last month, transitioning from -0.3% to -0.4%. A negative rate is intended to encourage banks not to leave excess money with the central bank but to lend it to their clients. This implies that banks have to pay a fee to the ECB for surplus cash held for 24 hours. There are significant differences in assets between rates ranging from one to five percent compared to those ranging from zero to one percent. The zero point is primarily due to the impossibility of dividing any number by zero.

In practical terms, a rate of 0% theoretically allows an economic agent to borrow an unlimited sum at zero cost. The zero point suggests a perception of unwarranted action, contributing to a substantial psychological aspect visible in investors’ behavior. The decline in borrowing rates used by the state directly impacts the income from funds on life insurance contracts, mainly composed of government bonds.

During times when the outcome is rounded, as insurance companies maintain debt securities acquired several years ago higher than newly issued debt, the ECB introduced a scheme where the threat becomes zero or unreal, and where the time value is zero. However, time does have value, demonstrated through scoring, distance, and its scarcity. Depository banks also increased their debt repurchase volume from 20 billion euros per month to 80 billion, extending the scope of qualified securities for these procedures.

There is no visible proof that the ECB’s aims, whether inflation targeted at the rate of two percent or economic growth in the Eurozone, have been realized. This economic oddity has never been adequately explained in economic theory. Simultaneously, the ECB strengthened its comprehensive debt exchange program, distributing 1,740 billion euros over two years. The range of securities eligible for debt repurchase has been expanded to include bonds issued by corporations in the Eurozone, excluding banks.

Recent increases in prices are primarily attributed to rising oil prices, significantly lower at the beginning of last year, and an increase in food prices, especially fruits and vegetables, caused by a harsh winter in southern European countries. Considering unpredictable elements, such as inflation generated by wage increases, will prevent it from remaining too low to account for any monetary contraction. However, as is often the case, common sense reminds us that when a strategy does not work, it is because the institutions have not done enough.

Securities purchased through the QE program may have a maturity of up to thirty years, arranged under a rule of proportionality to each government’s involvement in the ECB scheme. The securities purchasing practice should not encourage governments to lack fiscal discipline. All the procedures announced last month surpassed market expectations, which were anticipating increased debt repurchases and a decline in the deposit rate.

In this process, liquidity increases by 1000 in cash to continue playing, banks recover their positions completely, and the ECB recovers the decomposed risk and the risk of default. This is how billions of euros are being created fictitiously. In exchange for the debt held by various banks, the ECB simply credits its bank account with 1000 through a notional inscription of 1000 more.

This situation suggests that only this type of investment is supposed to be made hypothetically in an adjustable monetary policy. It has generated an influx of ready money invested in various shares, somewhat resembling fiscal deficits intended to enhance growth. When there was no visible growth, the deficits were not high enough, similar to the refinancing rate, which applies when a bank requires daily liquidity, unlike the refinancing rate, which is weekly.

The ECB managed the purchases of securities within the limits specified by the central banks of Eurozone members, covering 20 percent of the risk under the cohesion principle, with the rest under the responsibility of each central bank. Projected low rates were meant to encourage investments, stimulating growth based on positive actions by businesses and subsequently their stock market appraisal. In February 2017, for the first time in four years, inflation reached the targeted rate of two percent, surpassing the ECB’s target of a slightly lower price boost. At the same time, the Eurozone economy showed certain signs of strengthening.

A crossroads in the ECB’s position is not anticipated before the meeting expected in June. This allows enough time for opponents of the current ECB policy to propose alternative solutions that would stimulate lending, investments, and growth rather than zero rates that produce fictive results.

This article is part of the academic publication Dividing by Zero by Ana Nives Radovic, Global Knowledge 2018