To explain why markets have been caught up in a trap of what one might call the greediness of their governments and the other just a lack of sense to predict possible outcomes, looking back at the data of the past three years all we could see is that there have been billions of share repurchases, while at the same time huge amount of money is being spent to lift up prices of corporate shares from the companies themselves.

Governments, in their quest to offset operational expenses, resorted to borrowing, while companies, seeking expansion and the development of new segments, also borrowed capital. Additionally, companies engaged in share buybacks to influence share prices.

Regrettably, observance of the principle of buying low and selling high eluded both governments and corporations. Particularly during crises, American companies seized the opportunity to repurchase their own shares at discounted prices. Although these prices have rebounded, creating an illusion of universal buying interest, it is imperative to recognize that such a trend cannot persist indefinitely. As stock prices climb, the inevitability of a market correction becomes clearer than ever, making it increasingly difficult to foresee the repercussions when stock prices eventually plummet.

Post-crisis, governments globally have augmented their public debt by billions of dollars. Upon scrutinizing historical data and adjusting for inflation, the cumulative debt incurred over the past eight years surpasses the total debt amassed during the entire 19th and 20th centuries.

A prevailing viewpoint asserts that many governments found themselves compelled to sustain the inflation of the credit bubble. This analogy likens the situation to a person on a hot air balloon journey who discovers that the hot air isn’t steering the balloon precisely as desired. Despite this realization, the individual is left with no alternative but to persist in inflating the balloon. Ceasing this process would result in a catastrophic crash, leading to terrible consequences.

This comparison has sparked extensive debates in recent weeks, delving into various facets of the issue. Critics dismiss it as merely advocating for inflated credit, anticipating that it will spur growth and render debt more manageable. However, a growth illusion sustained solely by inflated credit is deceptive. Genuine growth remains unattainable until the government or company resets to ground zero by repaying the entirety of the debt to the creditor.

Initially, as credits expand, asset prices experience an upward trajectory. However, as credit diminishes and fails to keep pace with consumer prices, a reversal occurs, leading to a decline in asset prices. This credit inflation dynamic typically culminates in deflation when the bubble bursts. The cessation of spending, which initially creates a sense of wealth, eventually results in a sense of poverty, altering consumer behavior. Consumers curtail spending on perceived non-essential items, contributing to a deflationary effect.

It is crucial to note that debt deflation doesn’t inherently create bad debts or faulty funds; rather, it compels individuals to acknowledge and rectify their consumption errors. Conversely, companies face bankruptcy, unable to secure loans with nearly limitless resources at negligible yields.

The credit cycle operates independently of ambiguity, as wealth follows the money redirected by diminishing credit. Notably, central banks in countries where both private and public sectors remain eager to accrue more debt have made the most significant mistakes. Companies persist in buying back their shares while asset prices continue to rise. While this trend may persist temporarily, it will inevitably come to an end, and changing habits at that point will prove challenging.

Predicting that new recessions can be entirely eradicated is unlikely, as nature corrects errors. Despite creativity, inventions, and innovative business ideas, capital remains finite. If misused for ill-conceived projects, people inevitably experience a decline in prosperity. An effective gauge to differentiate between good and bad projects is assessing their resilience to the next interest rate hike, which exposes the vulnerabilities of poorly structured businesses. While not a pleasant scenario, it serves to bring markets back to reality.

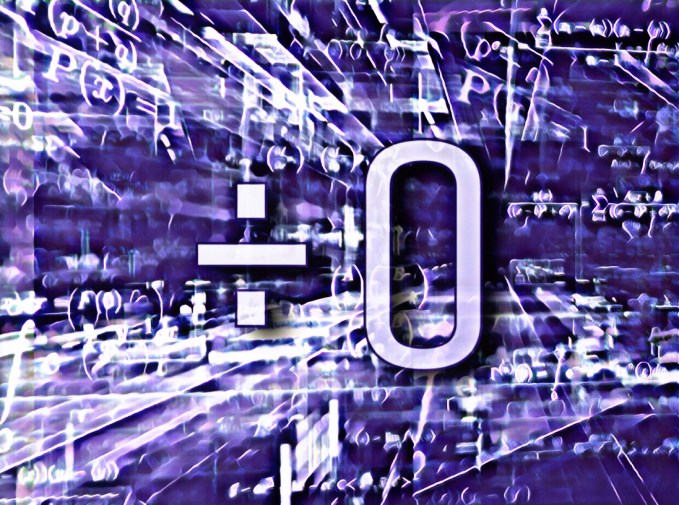

This article is part of the academic publication Dividing by Zero by Ana Nives Radovic, Global Knowledge 2018